Islam! And the dream of a world Caliphate.

Following up on his week of introducing Buddhism, Hinduism, Zoroastrianism, Christianity, and Miscellaneous Local Divinities, MacGregor gives us a week about the interactions of Power and Faith around the time of Mohammed, AD 600 or so. The two coins he looks at in this podcast tell several important stories: first, the career of Abd al-Malik, the 9th Caliph, the first such ruler of the Islamic world to extend his empire over a large region; second, Islam’s shift away from representations of people in their art; and third, the still-extant dream of an all-Islamic empire. This latter dream, though some apparently believe in it strongly, seems unlikely to me at this point, given what we’ve learned about the separation of church and state, and given the long history of an institution like the papacy being constantly under threat, having to defend itself all the time. On the other hand, who knows what Internet 2.0 will bring? Islam is a very seductive religion, it’s straightforward and logical, and if it can be a force for world-unification in a positive way in the years to come, then I say, bring on the pan-world Islamic Caliphate.

Significant for the world of art, of course, is the move you see in these two coins, from representing the ruler as a big, central, and powerful human, to showing only text. In this case, it’s an old Arabic script with a familiar line from the Qu’ran about “There is no god but Allah, and Mohammed is his prophet,” one of the five pillars of the faith (I believe). Just as the Jews never depicted their god, making the Jesus on the St. Mary Mosaic a bit unusual, so the Moslems never depict Allah, Mohammed, or any creature with a soul...and so Islamic art quickly became focused on vegetative shapes, and the world’s most glorious calligraphy. And so, literacy rose in a big way, because everyone needed to interact with the word of god that is the book, none of this “I’m the priest so only I am allowed to read the sacred text” you got in the west, and shortly after Abd al-Malik, in the 700s, say, when the Caliphate had moved from Damascus (where these coins were minted) to Baghdad, you had one of the best-educated, most advanced (ugh—that word!) civilizations in all history. I’ve always thought it was a shame they didn’t have much of a tradition of drama...but I can trade it for their medicine, astronomy, algebra, etc.

Easily seduced by encyclopedic attempts to organize vast amounts of data, I fell in love with the BBC/British Museum podcast series “A History of the World in 100 Objects.” So I scoured the Museum and am posting one object a day: my terrible iPhone photos and vague memories of what MacGregor & Co. had to say. If anything educational comes of this, just remember that it was all accomplished remotely, from Seattle, through podcasts, blogs, and an iPhone camera!

Monday, October 31, 2011

Friday, October 28, 2011

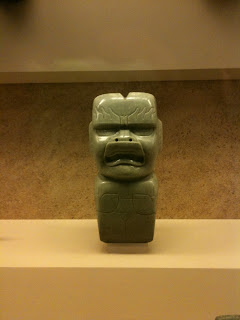

45. Arabian Bronze Hand (Yemen, AD 100-300)

Miscellaneous Local Gods!

Ha! Faked you out, you thought we were gonna talk about Islam today, didn’t you? Didn’t you! No, this object commemorates a local god, Talab, in a hill-town in Yemen, who inspired a wealthy person, also named Talab, to give his namesake god this remarkably life-like sculpture of a hand. (MacGregor’s hand surgeon expert points out that it’s modeled on a working hand, not a severed one, you can tell from the veins; and that the guy had broken his pinky at some point.) Of course, Yemen has been Islamic from the 600s on; but before that, it had bits of other mainstream religions, and before that, like most of the world, it was a strange welter of an infinite number of gods. Seems to me that Hinduism, with its reputed 33,333,333 gods, still operates along those lines; each river has its god, every hill and cloud; or else people are trained to see the numinous in all things. The advantage of such a system, seems to me, is that it must encourage respect for all elements of the world, because, whatever it is, even if it isn’t sacred to you, you’ve probably had enough experiences to know that it’s gotta be sacred to somebody. The disadvantage of such a system may be obvious: relativism. Mrs. Moore’s sound effect in the Malabar Caves.

If gods are really metaphors for values, then maybe the really fascinating thing is the process by which a person shifts gods. When Butterfly tells Pinkerton that she’s rejected her gods so she can worship side-by-side with him at his church, for example. (Of course, in that case there’s this tragic/pathetic thing where she goes back to her dad’s sword, at the end, giving up on the western god who abandoned her.) Isn’t that the same as those of us who switch our prejudices, against smoking or gay sex or what-not, and the head-spinning process involved there?

Ha! Faked you out, you thought we were gonna talk about Islam today, didn’t you? Didn’t you! No, this object commemorates a local god, Talab, in a hill-town in Yemen, who inspired a wealthy person, also named Talab, to give his namesake god this remarkably life-like sculpture of a hand. (MacGregor’s hand surgeon expert points out that it’s modeled on a working hand, not a severed one, you can tell from the veins; and that the guy had broken his pinky at some point.) Of course, Yemen has been Islamic from the 600s on; but before that, it had bits of other mainstream religions, and before that, like most of the world, it was a strange welter of an infinite number of gods. Seems to me that Hinduism, with its reputed 33,333,333 gods, still operates along those lines; each river has its god, every hill and cloud; or else people are trained to see the numinous in all things. The advantage of such a system, seems to me, is that it must encourage respect for all elements of the world, because, whatever it is, even if it isn’t sacred to you, you’ve probably had enough experiences to know that it’s gotta be sacred to somebody. The disadvantage of such a system may be obvious: relativism. Mrs. Moore’s sound effect in the Malabar Caves.

If gods are really metaphors for values, then maybe the really fascinating thing is the process by which a person shifts gods. When Butterfly tells Pinkerton that she’s rejected her gods so she can worship side-by-side with him at his church, for example. (Of course, in that case there’s this tragic/pathetic thing where she goes back to her dad’s sword, at the end, giving up on the western god who abandoned her.) Isn’t that the same as those of us who switch our prejudices, against smoking or gay sex or what-not, and the head-spinning process involved there?

Thursday, October 27, 2011

44. Hinton St. Mary Mosaic (England, AD 300-400) - NOT ON DISPLAY

Christianity!

In England, no less! MacGregor introduces this religion, of such weight in the west, in a sneaky way, through a mosaic (again, couldn’t find it on exhibit, I think it was under repair or curation or something) left in a Roman house in Dorset, England, the kind of house that might have had a swanky Hoxne pepper pot. It’s a mosaic tile, a standard channel of art for the Romans, and since Constantine in the 200s they’d been ok with Christians as one of the many weird religions in their empire. This image is one of the earliest representations of Jesus that exists; it may be they were reluctant to represent him, earlier, because Judaism (and they were all Jews) of course prohibits any depiction of the divine. Such a culture, where what’s divine is unrepresentable, has long co-existed, in the mideast and Mediterranean world, with the Rameses/Alexander approach of look at me, look at me, look at me, even if this is nothing like what I look like! (On the other hand, as MacGregor points out, what we know of Jesus is that he said “I am the Light and the Way and the Truth and the Life.” But what does that look like, exactly? And how do you render it in mosaic?

What did Jesus look like? No one knows, of course; there aren’t even any physical descriptions in the gospels. There’s probably lots of books tracing the history of how he’s been represented through the millenia; I fondly remember a silly zombie movie, made in Seattle about ten years ago, starring WASP Jesus, Hippie Jesus, Girl Jesus, and Angry Black Jesus. But I guess that’s the thing with such figures, you use them to talk about yourself, or at least something else that you know. In this mural, there’s a badly drawn Jesus, identified mostly because his name is written near his head; and next to him, Bellerophon is riding Pegasus up to battle the chimaera, and Bellerophon looks a lot like Jesus. Heroes morph very gradually, borrowing features from each other and evolving through the ages; thus Harry Potter has a lot in common with Frodo, although there are important differences, too, and when my cartoonist friend tried to make an image of me as well-known superhero ‘Captain Captions’ I believe he began by tracing the body of Captain Avenger, or some such. I didn’t mind.

In any event, the really odd thing about this Hinton St. Mary Mosaic is that Jesus was on the floor; you stepped on Him as you walked across the room. That probably wasn’t intended as a sign of disrespect, although pretty quickly I think art evolved to where that would be considered inappropriate. One of the many dangers of images; if you create an image, you can’t control it forever.

In England, no less! MacGregor introduces this religion, of such weight in the west, in a sneaky way, through a mosaic (again, couldn’t find it on exhibit, I think it was under repair or curation or something) left in a Roman house in Dorset, England, the kind of house that might have had a swanky Hoxne pepper pot. It’s a mosaic tile, a standard channel of art for the Romans, and since Constantine in the 200s they’d been ok with Christians as one of the many weird religions in their empire. This image is one of the earliest representations of Jesus that exists; it may be they were reluctant to represent him, earlier, because Judaism (and they were all Jews) of course prohibits any depiction of the divine. Such a culture, where what’s divine is unrepresentable, has long co-existed, in the mideast and Mediterranean world, with the Rameses/Alexander approach of look at me, look at me, look at me, even if this is nothing like what I look like! (On the other hand, as MacGregor points out, what we know of Jesus is that he said “I am the Light and the Way and the Truth and the Life.” But what does that look like, exactly? And how do you render it in mosaic?

What did Jesus look like? No one knows, of course; there aren’t even any physical descriptions in the gospels. There’s probably lots of books tracing the history of how he’s been represented through the millenia; I fondly remember a silly zombie movie, made in Seattle about ten years ago, starring WASP Jesus, Hippie Jesus, Girl Jesus, and Angry Black Jesus. But I guess that’s the thing with such figures, you use them to talk about yourself, or at least something else that you know. In this mural, there’s a badly drawn Jesus, identified mostly because his name is written near his head; and next to him, Bellerophon is riding Pegasus up to battle the chimaera, and Bellerophon looks a lot like Jesus. Heroes morph very gradually, borrowing features from each other and evolving through the ages; thus Harry Potter has a lot in common with Frodo, although there are important differences, too, and when my cartoonist friend tried to make an image of me as well-known superhero ‘Captain Captions’ I believe he began by tracing the body of Captain Avenger, or some such. I didn’t mind.

Me, your humble blogger

In any event, the really odd thing about this Hinton St. Mary Mosaic is that Jesus was on the floor; you stepped on Him as you walked across the room. That probably wasn’t intended as a sign of disrespect, although pretty quickly I think art evolved to where that would be considered inappropriate. One of the many dangers of images; if you create an image, you can’t control it forever.

Wednesday, October 26, 2011

43. Silver Plate Showing Shaipur II (Iran, AD 309-379)

Zoroastrianism!

As Meryl Streep the rabbi says at the beginning of Angels in America, “Eric? This a Jewish name?” I have to say “Zoroastrianism? This a major religion?” I thought he was going to talk about Judaism at this point. But I think he chose this object and this religion because it’s less familiar, and thus we’ll learn a little more. And he can use it to talk about Judaism obliquely, since Zoroastrianism lies behind all three of the big modern Western religions (he’s done Buddhism and Hinduism, so today it was time to go west, young man).

He starts by playing a couple chords of the great “Mountain Sunrise” from Richard Strauss, and then asks, “Just what did Zarathrustra spake, anyway?” ‘Cause not many people know. Although Zoroastrianism is still a legitimate religion, today, particularly in its homeland of Iran, it doesn’t have the numbers of the other main religions. The reason seems to be a political one, illustrating the intense need for a church/state division whenever possible—Zoroastrianism was the state religion of the Sassanian empire, in Iran after the Persian empire, and as such when Islam spread to Iran they got rid of the Sassanian regime and their religion along with them. (Caveat: apparently there are currently dedicated seats, in the Iranian parliament, for representatives of Iran’s Christian, Jewish, and surviving Zoroastrian communities.) With Christianity, even if an entire Christian kingdom got conquered, another survived to keep the faith.

Anyways, Zoroastrianism preceded the big three; its legacy to them includes the ideas that (unlike in Buddhism and Hinduism) time is linear and will end someday; that the universe is a big battlefield between good and evil; and the importance of old, wild-eyed prophets with scraggly beards. Fond as I am of the latter (Sir Ian McKellen knows I have a crush on him as Gandalf), I’m not so sure that I buy the teachings of these prophets, or the ideas of these religions...do good and evil really exist in the universe, or are those just concepts in human minds, defined entirely by humans? For instance, this plate, showing the Zoroastrian Sassanian King, the Shah of Shahs, slaying the ritual stag. Apparently that’s a metaphor for the victory of divine human kingship in league with the gods, overcoming the animalistic forces of darkness, etc. But how can a stag possibly be evil? Today, they’ve become synonymous with environmentalism and goodness. Sure, the king of an agricultural people will probably want to keep marauding animals at bay...but describing them as evil seems overstated to me.

We recently produced Mozart’s Magic Flute where I work at Seattle Opera, and we ran into an odd storytelling conundrum. The bass sings the role of Sarastro, a Zoroaster-like figure of wisdom and virtue, first introduced—Gozzi-like—as the enemy of the virtuous, potent, wholesome, suffering-mother type. We’re set up not to like Sarastro, and then this guy comes in and in a long recitative tells us we’re dumb, that Sarastro is really the quintessence of virtue; and that’s how the opera ends, with sunlight (Sarastro) triumphing over night (the Queen), good banishing evil for all time. (She’s evil, you see, because she cares more for trinkets/symbols of power than she does her own daughter.) And so the story doesn’t work, today. In the text, Sarastro is alarmingly a creature of the 18th century. He’s Thomas Jefferson to a tee...no longer acceptable as a hero, in a bold, cartoony, bust-of-Rameses kind of way, because we know he held slaves. I’m going out on a limb here but at the time, I bet everything he stood for was the right direction, and it may have been possible to be a slave-holder and a good person. But we’ve since lost that subtlety, and, much as I love our chief-storyteller for Magic Flute, I found the direction problematic. We allowed the audience to see what was dated and objectionable about the 18th century Zoroaster—fearsome misogyny, slave holding, and a fascistic need for complete devotion and obedience from the mindless sheep in his cult. (Prospero in The Tempest poses the exact same problems for modern theaters.) And then at the end, when the prince and princess are supposed to join his holy order, our director had them refuse and go off in a different direction. Now, a) there was much debate over whether the audience even figured out that that was the story we were telling, since it was done entirely in stage direction, not in the text, and if you were looking away or couldn’t see you wouldn’t know that that was happening. But b) for me, even though, of course, that’s the appropriate modern response for the prince and the princess, it made the whole plot kind of pointless...why did we bother to work so hard, through all Act 2, to get accepted by the order, only to decline the honor?

Of all the religions I’ve heard about, only Buddhism doesn’t present this kind of conundrum. Silence, it seems, never gets old.

As Meryl Streep the rabbi says at the beginning of Angels in America, “Eric? This a Jewish name?” I have to say “Zoroastrianism? This a major religion?” I thought he was going to talk about Judaism at this point. But I think he chose this object and this religion because it’s less familiar, and thus we’ll learn a little more. And he can use it to talk about Judaism obliquely, since Zoroastrianism lies behind all three of the big modern Western religions (he’s done Buddhism and Hinduism, so today it was time to go west, young man).

He starts by playing a couple chords of the great “Mountain Sunrise” from Richard Strauss, and then asks, “Just what did Zarathrustra spake, anyway?” ‘Cause not many people know. Although Zoroastrianism is still a legitimate religion, today, particularly in its homeland of Iran, it doesn’t have the numbers of the other main religions. The reason seems to be a political one, illustrating the intense need for a church/state division whenever possible—Zoroastrianism was the state religion of the Sassanian empire, in Iran after the Persian empire, and as such when Islam spread to Iran they got rid of the Sassanian regime and their religion along with them. (Caveat: apparently there are currently dedicated seats, in the Iranian parliament, for representatives of Iran’s Christian, Jewish, and surviving Zoroastrian communities.) With Christianity, even if an entire Christian kingdom got conquered, another survived to keep the faith.

Anyways, Zoroastrianism preceded the big three; its legacy to them includes the ideas that (unlike in Buddhism and Hinduism) time is linear and will end someday; that the universe is a big battlefield between good and evil; and the importance of old, wild-eyed prophets with scraggly beards. Fond as I am of the latter (Sir Ian McKellen knows I have a crush on him as Gandalf), I’m not so sure that I buy the teachings of these prophets, or the ideas of these religions...do good and evil really exist in the universe, or are those just concepts in human minds, defined entirely by humans? For instance, this plate, showing the Zoroastrian Sassanian King, the Shah of Shahs, slaying the ritual stag. Apparently that’s a metaphor for the victory of divine human kingship in league with the gods, overcoming the animalistic forces of darkness, etc. But how can a stag possibly be evil? Today, they’ve become synonymous with environmentalism and goodness. Sure, the king of an agricultural people will probably want to keep marauding animals at bay...but describing them as evil seems overstated to me.

We recently produced Mozart’s Magic Flute where I work at Seattle Opera, and we ran into an odd storytelling conundrum. The bass sings the role of Sarastro, a Zoroaster-like figure of wisdom and virtue, first introduced—Gozzi-like—as the enemy of the virtuous, potent, wholesome, suffering-mother type. We’re set up not to like Sarastro, and then this guy comes in and in a long recitative tells us we’re dumb, that Sarastro is really the quintessence of virtue; and that’s how the opera ends, with sunlight (Sarastro) triumphing over night (the Queen), good banishing evil for all time. (She’s evil, you see, because she cares more for trinkets/symbols of power than she does her own daughter.) And so the story doesn’t work, today. In the text, Sarastro is alarmingly a creature of the 18th century. He’s Thomas Jefferson to a tee...no longer acceptable as a hero, in a bold, cartoony, bust-of-Rameses kind of way, because we know he held slaves. I’m going out on a limb here but at the time, I bet everything he stood for was the right direction, and it may have been possible to be a slave-holder and a good person. But we’ve since lost that subtlety, and, much as I love our chief-storyteller for Magic Flute, I found the direction problematic. We allowed the audience to see what was dated and objectionable about the 18th century Zoroaster—fearsome misogyny, slave holding, and a fascistic need for complete devotion and obedience from the mindless sheep in his cult. (Prospero in The Tempest poses the exact same problems for modern theaters.) And then at the end, when the prince and princess are supposed to join his holy order, our director had them refuse and go off in a different direction. Now, a) there was much debate over whether the audience even figured out that that was the story we were telling, since it was done entirely in stage direction, not in the text, and if you were looking away or couldn’t see you wouldn’t know that that was happening. But b) for me, even though, of course, that’s the appropriate modern response for the prince and the princess, it made the whole plot kind of pointless...why did we bother to work so hard, through all Act 2, to get accepted by the order, only to decline the honor?

Of all the religions I’ve heard about, only Buddhism doesn’t present this kind of conundrum. Silence, it seems, never gets old.

Tuesday, October 25, 2011

42. Gold Coin of Kumaragupta 1 (India, AD 415-500)

Hinduism!

Now, I always thought that Hinduism was older than Buddhism, because the Upanishads and Puranas and Vedas predate the life of Gautama Siddartha (600 BC or so); but apparently I was wrong, those sacred texts aren’t exactly Hinduism, the way the Bible is Christianity or the Qu’ran is Islam. MacGregor introduces Buddhism first, and even mocks it gently for being a religion which is hard to represent; and he turns the next day to Hinduism, and presents it very much as a here-and-now religion, and who cares about whatever ancient sacred texts. Which seems to fit stereotypes I’ve always had of it.

He starts this podcast at a Hindu temple in London, where, at 4 pm every day, they wake up the resident gods by blowing on a horn. (I guess this is the sound of Hinduism, if silence is the sound of Buddhism.) The little statues you see all over every Hindu temple—and in many people’s homes, even cheap little Ganeshas like the one I had in college—are the actual god themselves, the way the host in Catholicism is magically the flesh and blood. The god comes down to inhabit your little local image. In many ways it’s the opposite of Buddhism—the domestication of the divine, gods who function much like household pets, where people feed them and dress them and put them to sleep and care for them lovingly all through their lives, instead of that Buddhist journey where, if you want to find god, you better strip away all that makes you animal and human, and you may be able to get part of the way yourself.

The Hindu object MacGregor is using here as a springboard to talk about the religion is a pair of gold coins, minted by King Kumaragupta—the Gupta dynasty, which dominated a big kingdom in India for a long time, was evidently a peer of the Roman and Byzantine Empires. This particular king took as his personal god his namesake Kumara, the god of War, a son of Shiva. On one of the coins you see him killing a horse. He did that, in real life as a ritual to cement his power; it was a much earlier, pre-Hindu ritual, where they’d let a beautiful stallion roam free and pure for a year (they’d somehow prevent it from mating), and then the king would sacrifice it publicly. Though a Hindu, Kumaragupta performed this ritual to get any residual people in his kingdom for whom that ritual held power to believe in him; and then, in the ultimate show of power, as with Alexander’s heirs, he minted coins. MacGregor tells this story of Kumaragupta’s quasi-Catholic acceptance of the beliefs of multiple faiths as the great strength of Hinduism, as it has been of so many imperial systems; and by implication criticizes forces currently at work, in the Hindu world, to limit the purview of the religion, to define Hinduism as “us and only us, the rest of you are heretics.” As was made clear when this series began, that kind of thinking is not what the world needs these days.

Now, I always thought that Hinduism was older than Buddhism, because the Upanishads and Puranas and Vedas predate the life of Gautama Siddartha (600 BC or so); but apparently I was wrong, those sacred texts aren’t exactly Hinduism, the way the Bible is Christianity or the Qu’ran is Islam. MacGregor introduces Buddhism first, and even mocks it gently for being a religion which is hard to represent; and he turns the next day to Hinduism, and presents it very much as a here-and-now religion, and who cares about whatever ancient sacred texts. Which seems to fit stereotypes I’ve always had of it.

He starts this podcast at a Hindu temple in London, where, at 4 pm every day, they wake up the resident gods by blowing on a horn. (I guess this is the sound of Hinduism, if silence is the sound of Buddhism.) The little statues you see all over every Hindu temple—and in many people’s homes, even cheap little Ganeshas like the one I had in college—are the actual god themselves, the way the host in Catholicism is magically the flesh and blood. The god comes down to inhabit your little local image. In many ways it’s the opposite of Buddhism—the domestication of the divine, gods who function much like household pets, where people feed them and dress them and put them to sleep and care for them lovingly all through their lives, instead of that Buddhist journey where, if you want to find god, you better strip away all that makes you animal and human, and you may be able to get part of the way yourself.

The Hindu object MacGregor is using here as a springboard to talk about the religion is a pair of gold coins, minted by King Kumaragupta—the Gupta dynasty, which dominated a big kingdom in India for a long time, was evidently a peer of the Roman and Byzantine Empires. This particular king took as his personal god his namesake Kumara, the god of War, a son of Shiva. On one of the coins you see him killing a horse. He did that, in real life as a ritual to cement his power; it was a much earlier, pre-Hindu ritual, where they’d let a beautiful stallion roam free and pure for a year (they’d somehow prevent it from mating), and then the king would sacrifice it publicly. Though a Hindu, Kumaragupta performed this ritual to get any residual people in his kingdom for whom that ritual held power to believe in him; and then, in the ultimate show of power, as with Alexander’s heirs, he minted coins. MacGregor tells this story of Kumaragupta’s quasi-Catholic acceptance of the beliefs of multiple faiths as the great strength of Hinduism, as it has been of so many imperial systems; and by implication criticizes forces currently at work, in the Hindu world, to limit the purview of the religion, to define Hinduism as “us and only us, the rest of you are heretics.” As was made clear when this series began, that kind of thinking is not what the world needs these days.

Monday, October 24, 2011

41. Seated Buddha (Pakistan, AD 100-300)

Buddhism!

MacGregor uses the next five objects to explore five major religions. He starts here in Gandhara, northern Pakistan, with a Buddha—a familiar, iconic image, post-enlightenment (or ‘awakening,’ as they insist it should be translated), with his earlobes stretched out by the heavy jewels he used to wear when he was a prince, with a big halo behind his head, and with his fingers in a “dharma chakra” pose of passing along the wheel of law. This very familiar image was actually new at the time, about 500-600 years into the life of the religion; prior to this period, no one ever depicted the Buddha in anthropomorphic form, they imaged the tree under which he sat for 49 days when he achieved enlightenment, or they imaged his footsteps...which are apparently still a sacred object of veneration among Buddhists, I didn’t know that.

The irony, of course, is that the highest value in the religion is nothing—doing nothing, needing nothing, becoming no thing. Yet the religion spread, and achieved power and world-permanence (domination is really an inappropriate word to use here) by all the conventional means: images like this one, giving human form and flesh to what seeks to transcend human form and flesh, and of course the luxury trade routes along which the religion first spread. It started farther south, in India, and came up here to Pakistan (then part of India) where the artists were really big on making these icons. MacGregor doesn’t talk about the big Buddhas recently destroyed by the Taliban. But he does include a good 15 seconds of silence, in his podcast—any more and I’m sure the producer of his radio show would have a heart-attack, since silence is death on radio or TV—in honor of the nothingness, the stillness, the peace that’s at the heart of Buddhism.

I’m pleased to say that it’s a peace that I find more and more fulfilling, the older I get.

MacGregor uses the next five objects to explore five major religions. He starts here in Gandhara, northern Pakistan, with a Buddha—a familiar, iconic image, post-enlightenment (or ‘awakening,’ as they insist it should be translated), with his earlobes stretched out by the heavy jewels he used to wear when he was a prince, with a big halo behind his head, and with his fingers in a “dharma chakra” pose of passing along the wheel of law. This very familiar image was actually new at the time, about 500-600 years into the life of the religion; prior to this period, no one ever depicted the Buddha in anthropomorphic form, they imaged the tree under which he sat for 49 days when he achieved enlightenment, or they imaged his footsteps...which are apparently still a sacred object of veneration among Buddhists, I didn’t know that.

The irony, of course, is that the highest value in the religion is nothing—doing nothing, needing nothing, becoming no thing. Yet the religion spread, and achieved power and world-permanence (domination is really an inappropriate word to use here) by all the conventional means: images like this one, giving human form and flesh to what seeks to transcend human form and flesh, and of course the luxury trade routes along which the religion first spread. It started farther south, in India, and came up here to Pakistan (then part of India) where the artists were really big on making these icons. MacGregor doesn’t talk about the big Buddhas recently destroyed by the Taliban. But he does include a good 15 seconds of silence, in his podcast—any more and I’m sure the producer of his radio show would have a heart-attack, since silence is death on radio or TV—in honor of the nothingness, the stillness, the peace that’s at the heart of Buddhism.

I’m pleased to say that it’s a peace that I find more and more fulfilling, the older I get.

Friday, October 21, 2011

40. Hoxne Pepper Pot (England, AD 350-400)

Spice!

From the home of a wealthy Roman in the west of England, not long before the Romans pulled out, comes this fun little pepper mill, complete with settings for ‘just a pinch’/‘spice it up’/‘rip the roof off my mouth’. Anticipating lots of little stories about the Great Silk Road and the Spice Route to the Spice Islands, MacGregor starts by speaking with a chef who explains why we crave this, and most, spices: the alkoid known as piperi, found in all peppers, kick-starts your salivary glands, making food taste better and aiding digestion; it kick-starts your sweat glands, helping regulate body temperature (particularly in warm climates, like the places where peppers usually grow); and it’s involved in a chemical process that helps the body convert glucose into heat, also regulating body temperature. It makes you feel good, and like salt it makes everything taste better. (Gotta admit, I had the best Jaipuri chicken last night at Kashmir, where they cover the meat in spices, bake it in a Tandoor, then sautee it in tomatoes, then in cream, then in yogurt...the number of different tastes, different chemical ideas, offered by this one yummy meal reminded me of a book filled with intriguing ideas, or an opera brimming with great voices and beautiful sounds. What a pleasure.)

The really crazy part is to imagine, not how the pepper pot, but how the pepper itself, would have gotten to Suffolk, where this whole Hoxne household was buried when they had to flee advancing Angles, Saxons, and Jutes in their hordes. (Who were the Jutes, anyway?) At the time, the nearest pepper was grown in India. The trade routes would have had to take it to the Indian Ocean, around to the Red Sea, by caravan across Egypt, in a boat across the Meditteranean, and then by land across Europe to get on a boat across the Channel so these people in the middle of nowhere could enjoy a tasty meal! And that was over a thousand years before the Europeans started getting really serious about establishing modern trade routes. I’d love to know what the local clods—the Celts, slaves, etc.—would have thought of the peppery meal if they’d had a chance to get a taste.

From the home of a wealthy Roman in the west of England, not long before the Romans pulled out, comes this fun little pepper mill, complete with settings for ‘just a pinch’/‘spice it up’/‘rip the roof off my mouth’. Anticipating lots of little stories about the Great Silk Road and the Spice Route to the Spice Islands, MacGregor starts by speaking with a chef who explains why we crave this, and most, spices: the alkoid known as piperi, found in all peppers, kick-starts your salivary glands, making food taste better and aiding digestion; it kick-starts your sweat glands, helping regulate body temperature (particularly in warm climates, like the places where peppers usually grow); and it’s involved in a chemical process that helps the body convert glucose into heat, also regulating body temperature. It makes you feel good, and like salt it makes everything taste better. (Gotta admit, I had the best Jaipuri chicken last night at Kashmir, where they cover the meat in spices, bake it in a Tandoor, then sautee it in tomatoes, then in cream, then in yogurt...the number of different tastes, different chemical ideas, offered by this one yummy meal reminded me of a book filled with intriguing ideas, or an opera brimming with great voices and beautiful sounds. What a pleasure.)

The really crazy part is to imagine, not how the pepper pot, but how the pepper itself, would have gotten to Suffolk, where this whole Hoxne household was buried when they had to flee advancing Angles, Saxons, and Jutes in their hordes. (Who were the Jutes, anyway?) At the time, the nearest pepper was grown in India. The trade routes would have had to take it to the Indian Ocean, around to the Red Sea, by caravan across Egypt, in a boat across the Meditteranean, and then by land across Europe to get on a boat across the Channel so these people in the middle of nowhere could enjoy a tasty meal! And that was over a thousand years before the Europeans started getting really serious about establishing modern trade routes. I’d love to know what the local clods—the Celts, slaves, etc.—would have thought of the peppery meal if they’d had a chance to get a taste.

Thursday, October 20, 2011

39. Admonitions Scroll (China, AD 500-800)

Influencing rulers through art!

I didn’t see this object, a painting on silk, because it’s too fragile and they don’t keep it out in the light. But MacGregor describes a fascinating piece that illustrates the relationship between artist and patron, courtier and ruler, as developed in Confucian China. Not long after the Han dynasty crumbled, a mentally deficient emperor was controlled by his unscrupulous wife and her powerful clan; one of her ministers, mandarins, I guess, wrote a poem for her describing the proper way for a woman to behave. That Confucian thing of ‘just set a good example;’ the poem wasn’t a direct criticism, and it doesn’t sound as though the poet was killed. Some time later, the leadership was in a similar situation; an emperor’s 30 year-old wife murdered him the night he joked about dumping her for someone younger. Pictures speak louder than words, apparently, so the response from the courtiers was this admonitions scroll, a painting admonishing the leading ladies of the kingdom to behave properly, and offering examples. The one MacGregor describes is evidently based on something that really happened: a traveling zoo or circus is exhibiting a bear to the emperor, but it gets loose and terrifies everyone. Two of the emperor’s wives are cringing, uselessly, as is the emperor himself; but the good wife has thrown herself between the bear and the emperor. Why can’t you all behave more like that?

MacGregor doesn’t tell us what happened to the painter. (Or, if this object were like the lacquer cup above, the team that created the painting.) The story does beg the question, though, about the proper relationship between leader and courtier, which has very often turned into patron and artist. Many 18th-century European operas, which are largely obsessed with defining the difference between a good ruler and a tyrant, are unperformable today (or at least, difficult for a modern audience to care about) because they’re basically propaganda for whoever paid for the original production. Artists flatter patrons, the way courtiers flatter those whose court they’re in. I’ve found there’s a very curious, always evasive balance, in a court (in my own way I’m an advisor to a person in power) because the courtier wants to be close to the leader, and yet wants to be independent; wants the leader to like him and prefer to have him around, yet wants the leader to respect his integrity and listen to him when he’s admonishing the leader. Plus, there are (or should be) multiple courtiers, and I don’t see any way for them not to be engaging in petty jealousies and rivalries and jockying for power among each other. It’s easier in a situation like that in Turandot, where the three ministers, Ping, Pang, and Pong, are a three-headed hydra, virtually indistinguishable from each other. On the other hand, the tyrant-princess hasn’t listened to anything they’ve said in years.

One other fun thing about the admonitions scroll is its midrash of commentors. MacGregor points out that, although it’s been around a long time, only the elite of the elite ever got a chance to view it; and many of them left comments on it, the way a little bit of the Torah gets midrash, commentaries surrounding it by the generations of rabbis. (Although in the case of the Torah, the original work is reproducible, unlike the Admonitions Scroll.) It does remind me of a trail of Facebook comments left on a posted photo...although one might hope the comments here are a bit more valuable, in terms of semantic significance, than those left on your typical Facebook post.

I didn’t see this object, a painting on silk, because it’s too fragile and they don’t keep it out in the light. But MacGregor describes a fascinating piece that illustrates the relationship between artist and patron, courtier and ruler, as developed in Confucian China. Not long after the Han dynasty crumbled, a mentally deficient emperor was controlled by his unscrupulous wife and her powerful clan; one of her ministers, mandarins, I guess, wrote a poem for her describing the proper way for a woman to behave. That Confucian thing of ‘just set a good example;’ the poem wasn’t a direct criticism, and it doesn’t sound as though the poet was killed. Some time later, the leadership was in a similar situation; an emperor’s 30 year-old wife murdered him the night he joked about dumping her for someone younger. Pictures speak louder than words, apparently, so the response from the courtiers was this admonitions scroll, a painting admonishing the leading ladies of the kingdom to behave properly, and offering examples. The one MacGregor describes is evidently based on something that really happened: a traveling zoo or circus is exhibiting a bear to the emperor, but it gets loose and terrifies everyone. Two of the emperor’s wives are cringing, uselessly, as is the emperor himself; but the good wife has thrown herself between the bear and the emperor. Why can’t you all behave more like that?

MacGregor doesn’t tell us what happened to the painter. (Or, if this object were like the lacquer cup above, the team that created the painting.) The story does beg the question, though, about the proper relationship between leader and courtier, which has very often turned into patron and artist. Many 18th-century European operas, which are largely obsessed with defining the difference between a good ruler and a tyrant, are unperformable today (or at least, difficult for a modern audience to care about) because they’re basically propaganda for whoever paid for the original production. Artists flatter patrons, the way courtiers flatter those whose court they’re in. I’ve found there’s a very curious, always evasive balance, in a court (in my own way I’m an advisor to a person in power) because the courtier wants to be close to the leader, and yet wants to be independent; wants the leader to like him and prefer to have him around, yet wants the leader to respect his integrity and listen to him when he’s admonishing the leader. Plus, there are (or should be) multiple courtiers, and I don’t see any way for them not to be engaging in petty jealousies and rivalries and jockying for power among each other. It’s easier in a situation like that in Turandot, where the three ministers, Ping, Pang, and Pong, are a three-headed hydra, virtually indistinguishable from each other. On the other hand, the tyrant-princess hasn’t listened to anything they’ve said in years.

One other fun thing about the admonitions scroll is its midrash of commentors. MacGregor points out that, although it’s been around a long time, only the elite of the elite ever got a chance to view it; and many of them left comments on it, the way a little bit of the Torah gets midrash, commentaries surrounding it by the generations of rabbis. (Although in the case of the Torah, the original work is reproducible, unlike the Admonitions Scroll.) It does remind me of a trail of Facebook comments left on a posted photo...although one might hope the comments here are a bit more valuable, in terms of semantic significance, than those left on your typical Facebook post.

Wednesday, October 19, 2011

38. Ceremonial Ballgame Belt (Mexico, AD 100-500)

Sports as Religion!

This large stone belt is the ceremonial version of a belt made of cloth or wicker which was worn, in Meso-America, in the oldest ball game known to history; it was a bit like soccer, only you apparently couldn’t kick the ball either, you had to bonk it with your hips. Oh, and the losing team were sacrificed to the gods. (Or was it the winning team?) If art has its origins in religion, than so does sport, and somehow the striving and communal accomplishment and chaos of these games developed as a metaphor for the religious understanding of these cultures, how they saw the workings of the universe. If you add that ultimate stake—one or the other of the teams will die—it is in fact a lot like life, isn’t it? That kind of blows your mind.

Philosophically, MacGregor’s interesting point here is about the role sport played in this Meso-American society and the role(s) it can play today. Which is, it’s hugely important to lots lots lots of people. Not me, perhaps, but I’ve given my life over to art, and so can imagine those for whom sport plays a similarly central role. In what other context do such large numbers of people come together, at one time and place, to concentrate together on something? Something esoteric, to be sure, the peregrinations of a rubber ball around a court, or whether or not a singer hits a high note. It’s probably only because the thing being concentrated on is so esoteric that so much attention can be focused. That is, in an election, or a bit of legislation, or the unveiling of a new product, we don’t all get together the same way to concentrate on what concerns us. Maybe it’s just the nature of drama.

In any event, games like this have been played in central America the longest, probably because they had rubber trees and figured out how to make rubber balls first! It is interesting to me that sport/recreation in Europe, before 1500, tended to be about hunting, or gladitorial games or bear-baiting, etc. And how quickly they took to soccer once they got it—how brilliantly, powerfully, it took its modern role at the center of huge numbers of men’s concept of what it means to be a man.

This large stone belt is the ceremonial version of a belt made of cloth or wicker which was worn, in Meso-America, in the oldest ball game known to history; it was a bit like soccer, only you apparently couldn’t kick the ball either, you had to bonk it with your hips. Oh, and the losing team were sacrificed to the gods. (Or was it the winning team?) If art has its origins in religion, than so does sport, and somehow the striving and communal accomplishment and chaos of these games developed as a metaphor for the religious understanding of these cultures, how they saw the workings of the universe. If you add that ultimate stake—one or the other of the teams will die—it is in fact a lot like life, isn’t it? That kind of blows your mind.

Philosophically, MacGregor’s interesting point here is about the role sport played in this Meso-American society and the role(s) it can play today. Which is, it’s hugely important to lots lots lots of people. Not me, perhaps, but I’ve given my life over to art, and so can imagine those for whom sport plays a similarly central role. In what other context do such large numbers of people come together, at one time and place, to concentrate together on something? Something esoteric, to be sure, the peregrinations of a rubber ball around a court, or whether or not a singer hits a high note. It’s probably only because the thing being concentrated on is so esoteric that so much attention can be focused. That is, in an election, or a bit of legislation, or the unveiling of a new product, we don’t all get together the same way to concentrate on what concerns us. Maybe it’s just the nature of drama.

In any event, games like this have been played in central America the longest, probably because they had rubber trees and figured out how to make rubber balls first! It is interesting to me that sport/recreation in Europe, before 1500, tended to be about hunting, or gladitorial games or bear-baiting, etc. And how quickly they took to soccer once they got it—how brilliantly, powerfully, it took its modern role at the center of huge numbers of men’s concept of what it means to be a man.

Tuesday, October 18, 2011

37. North American Otter Pipe (USA, 200 BC – 100 AD)

Smoking!

“Spice and vice,” MacGregor says, is the theme of his week, and he’s particularly intrigued by how mores and the culturally acceptable change over time. He began his ‘gay porn’ podcast of the day before commenting that a Rodin sculpture of a nekked male/female couple kissing was considered ‘unexhibitably’ erotic when created, at the turn of the century, thus collected by Mr. Warren of Sussex along with his impossible cup. (When the Warren Cup went on exhibit at the museum, a political cartoon had an ancient Roman at a market and the vendor asking whether he wanted to buy a straight cup or a gay one.) Smoking, needless to say, is a pastime which has provoked similarly varied attitudes, in recent years.

I’ve noticed over the years my own prejudices and attitudes shift about in mysterious ways. I wonder what it’d be like to have some that are fixed, really, truly fixed. Raised to be extremely homophobic, it took longer than it should but I have for the most part been able to let that go. Since 9/11, I’ve become absurdly prejudiced against automobiles; it’s an obsession, I realize that I take it too seriously, but since it’s both thought and feeling, I’m not quite in control of it. And who’s to say that I’m wrong...that one day, humans won’t look back on the dark time when we drove cars as we look back on other unfortunate episodes of Wahn, on eras that practiced human sacrifice or held slaves or committed genocides?

Something of the kind happened in the last decade around smoking. Tobacco, originally cultivated here in the Americas, swept the new world by storm by 1600. MacGregor has a glorious quote from King James (post 1603) denouncing smoking as “a custom loathsome to the eye, hateful to the nose, harmful to the brain, dangerous to the lungs, and in the black, stinking fume thereof, nearest resembling the horrible Stygian smoke of the pit that is bottomless.” I couldn’t agree more, and, going back ten years, I was at least as prejudiced against smokers as I currently am about those who depend on cars. But a funny thing happened: in Washington, as in California and New York and many other places, it was legislated that you couldn’t smoke in public places. And suddenly smokers were being herded up and discriminated against. And that made me more uncomfortable than their smoking had, originally. So there you go...we spent some time in Copenhagen, in 2006, where (as in much of Europe) everyone still smokes loudly and proudly. My friend and I concluded that it was the symbolism of a people who, if you try to tell them what to do, try to legislate how they behave, will by nature do exactly the opposite. Just like parents and kids.

I’ve never smoked, never touched a cigarette or pot to my lips; never taken any illegal drugs, indeed, never really been around any, never been offered any that I can remember. A sheltered life? Perhaps. Had I lived in the ancient north American culture that produced this cute little otter pipe, who knows, I probably would be like the MP MacGregor talks to on this podcast, an ardent defender of his smoking habit. (To his credit, he didn’t recommend that anyone start; but he’s not going to give up his pipe, it means too much to him by way of companionship, comfort, pastime.) The deal with the native American thing is that it was an important part of peace and other rituals; smoking was something sacred. This pipe was carved as a river otter, a charismatic and fascinating animal, one that may have been taken as a totem. And to smoke this pipe, you basically have to kiss the otter; it reminds me of Stephano’s oft-repeated line to Caliban in The Tempest, “Kiss the book, monster!” when he’s teaching him to drink from his bottle. A sweet custom, I’m sure...if you can get over the part where you’re giving yourself cancer, coating the inside of your body-temple with diseased filth and slime, killing yourself in an effort to look cool and fit in with losers.

“Spice and vice,” MacGregor says, is the theme of his week, and he’s particularly intrigued by how mores and the culturally acceptable change over time. He began his ‘gay porn’ podcast of the day before commenting that a Rodin sculpture of a nekked male/female couple kissing was considered ‘unexhibitably’ erotic when created, at the turn of the century, thus collected by Mr. Warren of Sussex along with his impossible cup. (When the Warren Cup went on exhibit at the museum, a political cartoon had an ancient Roman at a market and the vendor asking whether he wanted to buy a straight cup or a gay one.) Smoking, needless to say, is a pastime which has provoked similarly varied attitudes, in recent years.

I’ve noticed over the years my own prejudices and attitudes shift about in mysterious ways. I wonder what it’d be like to have some that are fixed, really, truly fixed. Raised to be extremely homophobic, it took longer than it should but I have for the most part been able to let that go. Since 9/11, I’ve become absurdly prejudiced against automobiles; it’s an obsession, I realize that I take it too seriously, but since it’s both thought and feeling, I’m not quite in control of it. And who’s to say that I’m wrong...that one day, humans won’t look back on the dark time when we drove cars as we look back on other unfortunate episodes of Wahn, on eras that practiced human sacrifice or held slaves or committed genocides?

Something of the kind happened in the last decade around smoking. Tobacco, originally cultivated here in the Americas, swept the new world by storm by 1600. MacGregor has a glorious quote from King James (post 1603) denouncing smoking as “a custom loathsome to the eye, hateful to the nose, harmful to the brain, dangerous to the lungs, and in the black, stinking fume thereof, nearest resembling the horrible Stygian smoke of the pit that is bottomless.” I couldn’t agree more, and, going back ten years, I was at least as prejudiced against smokers as I currently am about those who depend on cars. But a funny thing happened: in Washington, as in California and New York and many other places, it was legislated that you couldn’t smoke in public places. And suddenly smokers were being herded up and discriminated against. And that made me more uncomfortable than their smoking had, originally. So there you go...we spent some time in Copenhagen, in 2006, where (as in much of Europe) everyone still smokes loudly and proudly. My friend and I concluded that it was the symbolism of a people who, if you try to tell them what to do, try to legislate how they behave, will by nature do exactly the opposite. Just like parents and kids.

I’ve never smoked, never touched a cigarette or pot to my lips; never taken any illegal drugs, indeed, never really been around any, never been offered any that I can remember. A sheltered life? Perhaps. Had I lived in the ancient north American culture that produced this cute little otter pipe, who knows, I probably would be like the MP MacGregor talks to on this podcast, an ardent defender of his smoking habit. (To his credit, he didn’t recommend that anyone start; but he’s not going to give up his pipe, it means too much to him by way of companionship, comfort, pastime.) The deal with the native American thing is that it was an important part of peace and other rituals; smoking was something sacred. This pipe was carved as a river otter, a charismatic and fascinating animal, one that may have been taken as a totem. And to smoke this pipe, you basically have to kiss the otter; it reminds me of Stephano’s oft-repeated line to Caliban in The Tempest, “Kiss the book, monster!” when he’s teaching him to drink from his bottle. A sweet custom, I’m sure...if you can get over the part where you’re giving yourself cancer, coating the inside of your body-temple with diseased filth and slime, killing yourself in an effort to look cool and fit in with losers.

Monday, October 17, 2011

36. Warren Cup (Judea, AD 5-15)

Gay porn!

MacGregor uses this amazing embossed silver cup to introduce a series of objects telling stories of pleasure and recreation from two thousand years ago, and I suspect he starts with this one knowing it’ll grab people’s attention. I gotta confess I thought it was a little weird, in the museum, to have this explicit work of—let’s call it “erotic art”—front and center, with lots of kids milling about; but that just goes to show you how conservatively I’ve been socialized. Nah, it’s just a cup. The holy grail.

Presumably this belonged to a well-to-do Roman living in the Judea of King Herod, when Jesus was very small. MacGregor hypothesizes that the owner liked to host all-male dinner parties along the lines of Plato’s Symposium, and had this cup made (or purchased) for passing around at such gatherings. The cup itself is carefully encoded—one side shows a more idealized coupling, with two quasi-Greek adolescents in an odd, Kama Sutra-esque pose (above); the other a more realistic image of an older guy (you can tell ‘cause he’s got a beard) with a younger guy settling down on top of him with help from a sling or curtain.

If you look closely at the more realistic picture, you see a third guy peering around the door; MacGregor posits both an idealized/romantic interpretation, that that’s a peeping Tom there to heighten the erotic charge of the image, and the more realistic interpretation, that that’s a slave nervously answering a bell-call.

Anyway, the history of the cup is fascinating—at one point in the 20th century an offended US customs official in Boston even refused to allow it into the country. MacGregor points out that it was probably always controversial, since even in ancient Rome (or Roman Judea) it’s not like there were yearly pride parades. The artist must have used the trope of “Greek love,” all these ancient Greek haircuts and these overtones of the Symposium, to give the Roman user a charge of the exotic to go with the erotic.

One of MacGregor’s colleagues testifies on the podcast that she thinks this cup is one of the most beautiful objects in the museum, and that she intends to bring her daughter there and show it to her when it comes time to have ‘the talk’ and she wants her kid to understand homosexuality. Again, I suspect that’s in the podcast politically, to make a strong statement and head any outraged homophobes off at the pass. For myself, while I suspect we Americans are currently giving kids lots of terribly mixed-up and confusing messages about love and sex and gays and straights, something in me still feels that it’s better to keep kids away from porn. Not sure whether I’d want my dependants to encounter this object. Although, thinking it through as I write this, the important part is less whether they encounter it or not—assuming they’re going to be citizens of the world, they’ll encounter it eventually. More important is probably the attitude with which I give (or deny) them permission to acknowledge or participate in what this object represents. (I’ll never forget, as a teenager, noticing my father’s appraisal—and dismissal—of a not-particularly great piece of erotic art we encountered somewhere; I remember that he acknowledged it, wasn’t very impressed by it, and moved on. Nothing special.) After all, that’s what’s important to a kid—who WE are, as a family, not who THEY were (the people who made the object).

MacGregor uses this amazing embossed silver cup to introduce a series of objects telling stories of pleasure and recreation from two thousand years ago, and I suspect he starts with this one knowing it’ll grab people’s attention. I gotta confess I thought it was a little weird, in the museum, to have this explicit work of—let’s call it “erotic art”—front and center, with lots of kids milling about; but that just goes to show you how conservatively I’ve been socialized. Nah, it’s just a cup. The holy grail.

Presumably this belonged to a well-to-do Roman living in the Judea of King Herod, when Jesus was very small. MacGregor hypothesizes that the owner liked to host all-male dinner parties along the lines of Plato’s Symposium, and had this cup made (or purchased) for passing around at such gatherings. The cup itself is carefully encoded—one side shows a more idealized coupling, with two quasi-Greek adolescents in an odd, Kama Sutra-esque pose (above); the other a more realistic image of an older guy (you can tell ‘cause he’s got a beard) with a younger guy settling down on top of him with help from a sling or curtain.

If you look closely at the more realistic picture, you see a third guy peering around the door; MacGregor posits both an idealized/romantic interpretation, that that’s a peeping Tom there to heighten the erotic charge of the image, and the more realistic interpretation, that that’s a slave nervously answering a bell-call.

Anyway, the history of the cup is fascinating—at one point in the 20th century an offended US customs official in Boston even refused to allow it into the country. MacGregor points out that it was probably always controversial, since even in ancient Rome (or Roman Judea) it’s not like there were yearly pride parades. The artist must have used the trope of “Greek love,” all these ancient Greek haircuts and these overtones of the Symposium, to give the Roman user a charge of the exotic to go with the erotic.

One of MacGregor’s colleagues testifies on the podcast that she thinks this cup is one of the most beautiful objects in the museum, and that she intends to bring her daughter there and show it to her when it comes time to have ‘the talk’ and she wants her kid to understand homosexuality. Again, I suspect that’s in the podcast politically, to make a strong statement and head any outraged homophobes off at the pass. For myself, while I suspect we Americans are currently giving kids lots of terribly mixed-up and confusing messages about love and sex and gays and straights, something in me still feels that it’s better to keep kids away from porn. Not sure whether I’d want my dependants to encounter this object. Although, thinking it through as I write this, the important part is less whether they encounter it or not—assuming they’re going to be citizens of the world, they’ll encounter it eventually. More important is probably the attitude with which I give (or deny) them permission to acknowledge or participate in what this object represents. (I’ll never forget, as a teenager, noticing my father’s appraisal—and dismissal—of a not-particularly great piece of erotic art we encountered somewhere; I remember that he acknowledged it, wasn’t very impressed by it, and moved on. Nothing special.) After all, that’s what’s important to a kid—who WE are, as a family, not who THEY were (the people who made the object).

Friday, October 14, 2011

35. Head of Augustus (Sudan, 27-25 BC)

Roman Empire!

Although the basic function of this big, striking head of Augustus is similar to the PR effect of the giant stone Rameses II, since it’s Augustus it’s worth pausing (the way we did over the Greeks with the Elgin Marbles) to say—this guy was a really big deal, and the change that happened on his watch is one of the main changes in human history. The transformation from Republic to Empire. I’m sure it’s happened in many other times and places; heck, as my great idol and role model Gore Vidal spent a lifetime pointing out (before going nuts), it happened in a big way in 20th century America. And those Star Wars prequels would have been worthwhile if they had gotten this story right, or interesting. A Republic, which is theoretically most concerned with the freedom and welfare of the people who live there, becomes an Empire, which is mostly interested in dominating its colonies and extending its domain and way of life. As mentioned before, unlike the Persian Empire, the Roman one tried its hardest to make all of Europe (and bits of Africa and the Mideast) into Rome, where one does like the Romans; just look at the mess they made of weekday names and month names, up north.

MacGregor and friends point out that Caesar Augustus, aka Octavian, must have been one of the greatest and most skillful politicians who ever lived, to be able to get rid of (or at least neuter) the Senate and the other triumvirs and create the structure where there’d be one (hereditary, I guess, although did that ever even happen?) emperor on the throne. Certainly the PR campaign that came up with the idea of sending this head out all over the empire was carefully considered; it’s almost a cartoon of the ideal god-leader humanoid. I remember being dazzled by this sculpture when I first came to the museum, many years ago. My picture from that trip has different color temperatures:

The fun thing about the object is that they found this particular head buried in the sand in northern Sudan. That was the border of the Roman empire to the south, the way Hadrian’s Wall was the boundary to the north, and as a sign of disrespect the Kushites in that upper part of the Nile buried this symbol of Roman power beneath the threshold of a temple, so that everyone would literally be stepping on Augustus to go in to where they worshipped. Even so, whether celebrated or despised, the head survived.

Although the basic function of this big, striking head of Augustus is similar to the PR effect of the giant stone Rameses II, since it’s Augustus it’s worth pausing (the way we did over the Greeks with the Elgin Marbles) to say—this guy was a really big deal, and the change that happened on his watch is one of the main changes in human history. The transformation from Republic to Empire. I’m sure it’s happened in many other times and places; heck, as my great idol and role model Gore Vidal spent a lifetime pointing out (before going nuts), it happened in a big way in 20th century America. And those Star Wars prequels would have been worthwhile if they had gotten this story right, or interesting. A Republic, which is theoretically most concerned with the freedom and welfare of the people who live there, becomes an Empire, which is mostly interested in dominating its colonies and extending its domain and way of life. As mentioned before, unlike the Persian Empire, the Roman one tried its hardest to make all of Europe (and bits of Africa and the Mideast) into Rome, where one does like the Romans; just look at the mess they made of weekday names and month names, up north.

MacGregor and friends point out that Caesar Augustus, aka Octavian, must have been one of the greatest and most skillful politicians who ever lived, to be able to get rid of (or at least neuter) the Senate and the other triumvirs and create the structure where there’d be one (hereditary, I guess, although did that ever even happen?) emperor on the throne. Certainly the PR campaign that came up with the idea of sending this head out all over the empire was carefully considered; it’s almost a cartoon of the ideal god-leader humanoid. I remember being dazzled by this sculpture when I first came to the museum, many years ago. My picture from that trip has different color temperatures:

The fun thing about the object is that they found this particular head buried in the sand in northern Sudan. That was the border of the Roman empire to the south, the way Hadrian’s Wall was the boundary to the north, and as a sign of disrespect the Kushites in that upper part of the Nile buried this symbol of Roman power beneath the threshold of a temple, so that everyone would literally be stepping on Augustus to go in to where they worshipped. Even so, whether celebrated or despised, the head survived.

Thursday, October 13, 2011

34. Han Lacquer Cup (China, AD 4)

State-sponsored Arts & Crafts!

This remarkable object was a gift, manufactured centrally in the capitol (not sure whether it was Beijing in those days) and then distributed en masse to various regional governors, who could use it to boast of their intimacy with the emperor, etc. when guests at their dinners drank from the cup. It’s a high-status object, the kind of gift that bestows prestige and strengthens social ties, and the thing MacGregor likes so much about it is the little caption plate listing the object’s credits: “Wooden core by Li, Lacquering by Yi, Top Coat Lacquering by Dang, Handles by Gu,” etc. True, it’s an extremely complicated proposition to make a large object like this (it’s a little bigger than my hand) out of lacquer, which is sap gathered from a tree. But only the Chinese, it’s implied, would find a way to build a bureacracy and mass-produce an object that embodies the essence of high-quality craftsmanship.

I’m guessing this topic will come up again and again as we get closer to the modern period. We want to have our cake and eat it too: we want gorgeous, unique objects, each individually crafted with love; and we want them cheaply mass-produced, so that everybody in the world can have one. Which is it going to be? Err too much on the one side of the equation, and nothing works and life is quirky, strange, and uncomfortable; err too much to the other extreme, and lose your soul. I work in an art form that, economically speaking, should have gone away with the destruction of the medieval guilds—there’s no good reason to take the time and care and fussing over every detail of an opera, the way we do. Or we should mass-produce it, in which case we’d be making movies, not operas. Which of you, I wonder, bother to sit through every minute of the credits at the end of the movies you enjoy, out of respect for the long list of artists who worked together to mass-produce the thing you just enjoyed?

Another view of the cup:

This remarkable object was a gift, manufactured centrally in the capitol (not sure whether it was Beijing in those days) and then distributed en masse to various regional governors, who could use it to boast of their intimacy with the emperor, etc. when guests at their dinners drank from the cup. It’s a high-status object, the kind of gift that bestows prestige and strengthens social ties, and the thing MacGregor likes so much about it is the little caption plate listing the object’s credits: “Wooden core by Li, Lacquering by Yi, Top Coat Lacquering by Dang, Handles by Gu,” etc. True, it’s an extremely complicated proposition to make a large object like this (it’s a little bigger than my hand) out of lacquer, which is sap gathered from a tree. But only the Chinese, it’s implied, would find a way to build a bureacracy and mass-produce an object that embodies the essence of high-quality craftsmanship.

I’m guessing this topic will come up again and again as we get closer to the modern period. We want to have our cake and eat it too: we want gorgeous, unique objects, each individually crafted with love; and we want them cheaply mass-produced, so that everybody in the world can have one. Which is it going to be? Err too much on the one side of the equation, and nothing works and life is quirky, strange, and uncomfortable; err too much to the other extreme, and lose your soul. I work in an art form that, economically speaking, should have gone away with the destruction of the medieval guilds—there’s no good reason to take the time and care and fussing over every detail of an opera, the way we do. Or we should mass-produce it, in which case we’d be making movies, not operas. Which of you, I wonder, bother to sit through every minute of the credits at the end of the movies you enjoy, out of respect for the long list of artists who worked together to mass-produce the thing you just enjoyed?

Another view of the cup:

Wednesday, October 12, 2011

33. Rosetta Stone (Egypt, 196 BC)

Translation!

The most famous object in the British Museum may tell two stories about great cultures clashing—the Greeks and Egyptians, when it was created, and the French and English, when it was unearthed—but mostly it’s great because it symbolizes DECODING, translation, in the most dramatic way possible. As a professional translator/interpreter, my bosom swells with pride to think of how crucial our work is, how ancient its tradition, how magical it is. It’s not about WHAT you’re translating. In my case, I mostly translate old opera libretti; in the Rosetta Stone, we’re talking about one of those 1040 Tax Return guides, rules about exemptions available to farmers and gamblers and clergymen, that kind of thing. I mean, who cares? Except that the translator had to care, at least long enough to get the text from one language into the next.

What I love about translating is that when you’re qualified, it just happens. You just think the thought, and the words come out in whatever language is required by the situation. There’s something extremely satisfying, fulfilling, magical about that, when you get to that place of complete trust and confidence in your own ability to listen to or read in another language and know what’s going on, and how best to render that same thought in a parallel language. Ever since I started studying French when I was 12, I’ve been blessed with a facility for it; but it’s like a muscle, that’s what’s cool about it. At some point you train the muscles to the place where, sure, you can bike from Seattle to Portland. The same way, you train your brain so that, sure, you can hop back and forth across the English Channel; or, in the Rosetta Stone’s case, the Mediterranean. I hereby salute all translators, all those who build bridges among people using language!

The historical significance of the Rosetta Stone is that the document carved on this rock allowed scholars to decode the ancient Egyptian written language. This tax code, issued under one of the Ptolomaic kings who (speaking Greek) ruled Egypt in the centuries after Alexander the Great, was written in Greek, for the rulers, and in Demotic (a phonetic alphabet for the Egyptian language, so that it was relevant to the people in Egypt) and in hieroglyphics, as a concession this weak King Ptolomey was making to the powerful Egyptian priestly class. (By this point in history, hieroglyphics were basically obsolete—they’re pictographs, and phonic alphabets are much easier to use. But by including them here, Ptolomey was able to make the priests feel important.)

When Napoleon’s men, trying to conquer Egypt from the Ottomans before the British did in the early 19th century—both racing to dominate the eventual Suez Canal)—unearthed the stone, it took both a French scholar (Champollion) and an English one (Young), cooperating, to decipher it. But would their respective nations ever cooperate on anything, for example, improving the situation for the people who lived in Egypt at the time? Not bloodly likely, mon vieux!

The most famous object in the British Museum may tell two stories about great cultures clashing—the Greeks and Egyptians, when it was created, and the French and English, when it was unearthed—but mostly it’s great because it symbolizes DECODING, translation, in the most dramatic way possible. As a professional translator/interpreter, my bosom swells with pride to think of how crucial our work is, how ancient its tradition, how magical it is. It’s not about WHAT you’re translating. In my case, I mostly translate old opera libretti; in the Rosetta Stone, we’re talking about one of those 1040 Tax Return guides, rules about exemptions available to farmers and gamblers and clergymen, that kind of thing. I mean, who cares? Except that the translator had to care, at least long enough to get the text from one language into the next.

What I love about translating is that when you’re qualified, it just happens. You just think the thought, and the words come out in whatever language is required by the situation. There’s something extremely satisfying, fulfilling, magical about that, when you get to that place of complete trust and confidence in your own ability to listen to or read in another language and know what’s going on, and how best to render that same thought in a parallel language. Ever since I started studying French when I was 12, I’ve been blessed with a facility for it; but it’s like a muscle, that’s what’s cool about it. At some point you train the muscles to the place where, sure, you can bike from Seattle to Portland. The same way, you train your brain so that, sure, you can hop back and forth across the English Channel; or, in the Rosetta Stone’s case, the Mediterranean. I hereby salute all translators, all those who build bridges among people using language!

The historical significance of the Rosetta Stone is that the document carved on this rock allowed scholars to decode the ancient Egyptian written language. This tax code, issued under one of the Ptolomaic kings who (speaking Greek) ruled Egypt in the centuries after Alexander the Great, was written in Greek, for the rulers, and in Demotic (a phonetic alphabet for the Egyptian language, so that it was relevant to the people in Egypt) and in hieroglyphics, as a concession this weak King Ptolomey was making to the powerful Egyptian priestly class. (By this point in history, hieroglyphics were basically obsolete—they’re pictographs, and phonic alphabets are much easier to use. But by including them here, Ptolomey was able to make the priests feel important.)

When Napoleon’s men, trying to conquer Egypt from the Ottomans before the British did in the early 19th century—both racing to dominate the eventual Suez Canal)—unearthed the stone, it took both a French scholar (Champollion) and an English one (Young), cooperating, to decipher it. But would their respective nations ever cooperate on anything, for example, improving the situation for the people who lived in Egypt at the time? Not bloodly likely, mon vieux!

Tuesday, October 11, 2011

32. Pillar of Ashoka (India, about 238 BC)

Ashoka! Since MacGregor on Alexander got me reminiscing about dumb movies I’ve seen, the same is true of Ashoka; we had an endless Bollywood epic, full of mediocre songs and splashy dance sequences, about ten years ago at our Seattle International Film Festival. (Michael Wood somehow got rights to quote this film in his The Story of India PBS/BBC deal...a watchable program, if not revelatory.) I remember Asoka trying to show the conversion of this interesting character from a bloodthirsty tyrant, typical warlord, to a benevolent figure enlightened by the same Eastern wisdom that would empower both Buddhism and Hinduism; in the case of the film’s plot, as I remember, the conversion was driven by Ashoka realizing he was responsible for the death of his own children, that kind of thing. (Memory is a bit vague, sorry.) MacGregor doesn’t recall a reason for the conversion, but he’s clearly entranced by the concept of a warlord who becomes a figure of benevolence, and that’s what this pillar was about: an edict, the word from the ruler, that went out (they didn’t have newspapers in those days) carved on these little rocks that they’d set up in all the major crossroads and/or market areas. Others have been found with this same inscription on it. MacGregor compares Ashoka’s approach to that of the current leadership of Bhutan, where there’s this beautiful idea of measuring Gross National Happiness, instead of Gross National Product. I think it’s a line of thought that’s worth pursuing.